FRANK CHLUMSKY

In 1978, Italy’s most celebrated and still best-selling singer, Mina, retired from public life for good. She was at the height of her career — her girlish, early image had evolved into that of a scintillating, soul-sick diva. She brazenly adopted cigarettes and mini-skirts as part of her emancipated image and sported a sexy, alien-esque look which featured shaved eyebrows, heavy black eye makeup, and a wild, undulating mane of fiery, artificial orange hair. She had been called “greatest singer in the world” by Louis Armstrong, and Sarah Vaughan had said that, had she not been born with her own voice, she’d “like to have the voice of a young Italian girl named Mina.” Both her lyrical themes (lust and infidelity) and her personal life (a widely publicized affair with a married man) had branded her an iconoclast in an Italy whose media was controlled and regulated by the Catholic Christian Democratic Party; 14 years before her public retirement, she had even been banned from the state-sponsored RAI, Italy’s largest television and radio broadcaster. Yet even national censorship could not erase Mina from the spotlight — that would be her own doing.

Mina – Tintarella di luna – 1959 | Source: Miloš 02/YouTube

Mina had strangely never achieved much exposure in the United States, but to put her retirement in American terms, it would be as if the Madonna of 1991 had renounced the stage after the Blond Ambition tour, or if Cardi B were to retire to a Parisian apartment and refuse to see anyone. When I began studying Italian in college, I looked to pop-culture and music — the things that had always interested me about my own culture — as my point of entry to the language. I was dismayed to find that a country whose language so naturally lent itself to music had managed to produce such a barren yet vast contemporary landscape of churned-n’-burned The X Factor winners and fifth rate rappers.

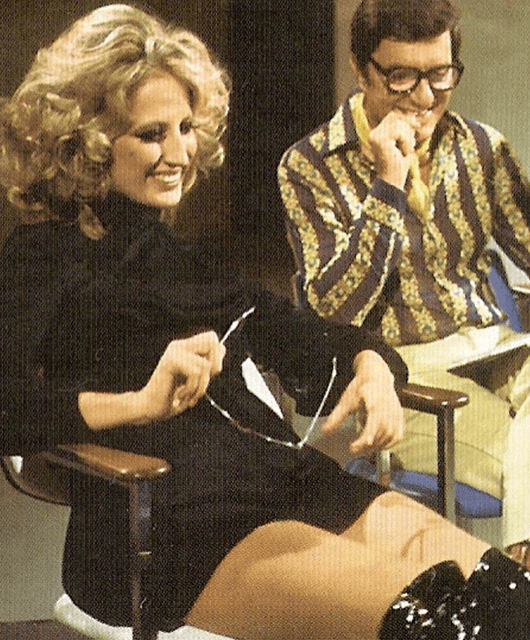

Mina Mazzini with Lelio Luttazzi | Source: Wikipedia

The shadow of Mina, however, hung over Italy like a ghost. When I eventually studied in Italy, it was apparent that any dinner table or classroom conversation about popular music began and ended with Mina, so much so that it seemed to go without saying in a sort of tacit reverence. I would sometimes ask about her — to my Florentine host-mother, to my chain-smoking, communist professor — pretending to only have only “heard” of her and not to have devoured her discography years before I had even arrived in Italy. They, in that characteristically Italian way, would respond with a stupefied gesture of supplication, as if to call upon the gods for the words to explain. Imparagonabile. Incomparable. No voice was as powerful, no image was as compelling. She is still alive, nearing 80, and regularly releases new music. But in the public eye, the Mina of 1978 is preserved in amber.

Mina – Ancora ancora ancora (1978) | Source: Dario Video Mina Fan/YouTube

Self-imposed exile is pretty badass. Well, on the condition that one is exiling oneself from somewhere that would already appear to be pretty great. In Mina’s case, she was where every aspiring singer would want to be. Why she gave it up — burnout, or stage-fright, or the understandable desire to once again lead a normal life — doesn’t so much matter, but its aftereffects do, especially in 2019 when the lines between public profile and private person are more blurred than ever.

I stop short of claiming that the rejection of fame is relevant simply because nowadays “everyone wants to be famous.” I’m allergic to this kind of undue nostalgia for the supposed humility and moral character of bygone eras, and I’m not convinced that fame is any more seductive now than it was 60 years ago. It’s simply more accessible, and naturally, more people than ever are grabbing at it.

When we bemoan “celebrity culture,” we tend to be lamenting a perceived erosion of standards and relaxation of the fame’s barriers to entry. This is like when vinyl-enthusiasts remind you at every turn that The Beatles had more musical substance than One Direction, or that Ariana Grande is a less gifted vocalist than Aretha Franklin. No shit. When all culture is “content,” I think we should really be concerning ourselves with the level of intrigue that would-be celebrities are bringing to their fame.

Why do any of us relate to superstars? In the best of them, we glean the greatness and the tragedy of our own existence.

I love celebrities, and have since the fifth grade. In those days I used to devour my grandmother’s issues of The National Enquirer, a publication which knows its demographic (“DYING CHER: BROKE & ALONE,” in a nicely-readable 64-point bold font). Its flagrant, flaming trash was a revelation to me, and the journalistic integrity of its reporting was inspiring in its disregard. When I got off the hard stuff, I moved to less hallucinatory substances like the E! Network and People. This is when the world was still was still wracking its collective brain over the problem of Paris Hilton, my generation’s first “famous for being famous” celebrity. These “news” outlets cultivated in me a degree of low-grade cultural literacy that would serve me well at trivia nights and college-dormitory dinner tables.

Paris Hilton On The Public’s Misconception Of Her & More (Exclusive): Access Hollywood | Source: © Access Hollywood/YouTube

As a gay man, I suppose it’s not surprising that I also liked the scandal of celebrity. But as a soft-core Catholic, I also admired the Pagan pageantry of it all. I thought it was no mistake that “icons” were “idolized:” all the greats had something of a mythic personal legend: Maria Callas: the myopic, pudgy soprano turned tragic diva, who had the love of everyone but the man she wanted it from the most, and who would die a recluse in Paris; Britney Spears: the publicly deflowered and defiled virgin, sent to the slaughterhouse by fame like a fattened calf.

Madonna’s Sex Book | Source: © Abe Books

Unsurprising, too, that Madonna has always been my favorite. What could a shy gay boy from the Midwest relate to in a superstar? The Italian-Catholic thing, sure, and a little bit of the Michigan thing. Above all it was the personal qualities, perceived or otherwise. I was awed by her ambition, but also attracted to her bitchiness. In interviews, Madonna never possessed a quippy, biting wit, but an awkward acerbity that seemed to belie her confidence. Even her provocations — the most daring of which was the 1992 Sex book — seemed to me a defiant sneer at a world that could not understand her, that she could not connect with. There is something of a real misfit. Why do any of us relate to superstars? In the best of them, we glean the greatness and the tragedy of our own existence.

Mina was one of these stars. Her powerful voice and melodramatic stylings gave a soundtrack to the growing pains of Italy in the mid-20th-century as it witnessed violent political upheaval and negotiated its conservative mores with sexual revolution and glamour of consumerism. Even for me, a non-Italian, I felt something of an ineffable personal connection with Mina when I first came across her in the mid 2010’s via YouTube and Wikipedia, and eventually memorized her lyrics. And in the age of overexposure, I thought her self-exile was pretty badass as well.

Why [Mina] gave it up — burnout, or stage-fright, or the understandable desire to once again lead a normal life — doesn’t so much matter, but its aftereffects do, especially in 2019 when the lines between public profile and private person are more blurred than ever.

Mina – Oggi sono io | Source: © Mina Mazzini Official/YouTube

The departure of Mina happened in a very different time (and country), when the world of celebrity was, at least theoretically, a meritocracy of talent. We’ve made leaps and bounds since then. Social media solved the conundrum of gratuitous celebrity by putting a fine point on the commercial packaging of a star. In 2005, Paris Hilton was labelled an air-headed, no-talent, good-for-nothing tele-bimbo. In 2019, she is — not incorrectly — recognized as a smart businesswoman for effectively hacking her way into the public consciousness. For a tabloid devotee like myself, this new landscape has exciting dystopian possibilities. More and more, however, it seems we are growing fatigued.

Or at least I am. Shamefully, I know far less about popular culture now than I did when I was 10. I dropped off shortly after the advent of YouTube celebrities, when I realized that there were simply too many famous people to possibly keep track of. In many ways, I have become that guy who believes that everything was more exciting in eras he never lived. Can anyone deny that fame has lost some of its weight? Like anything, it has lost its value as it has become more widely available.

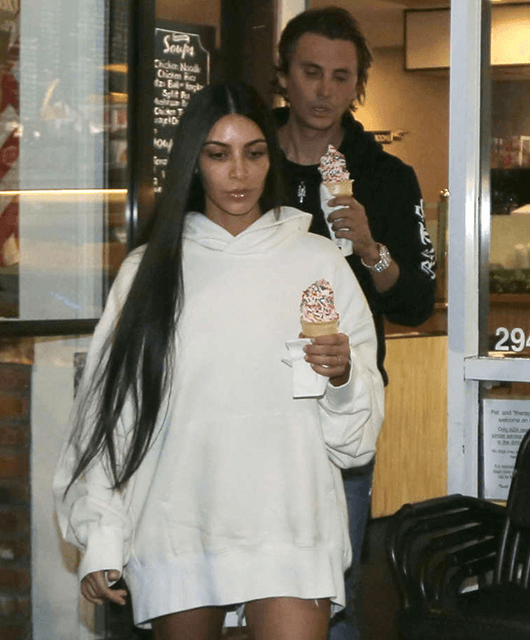

Paparazzi shot of Kim Kardashian leaving the frozen yogurt store following the armed robbery episode | Source: © The Cut

But what if celebrities were to follow Mina’s example? What if Ariana Grande were to become a recluse? That would be a story. Out of nowhere, her entire narrative would be re-written, her work would be re-evaluated, she would become a mystery. We’ve seen brief glimpses of this effect recently in the form of social-media silences. The dramatic armed robbery of Kim Kardashian in her Paris hotel room in 2016 sparked one such virtual hiatus. While it only took Kardashian a month to resume regular posting to her accounts, that month of silence — even the gorgeous paparazzi shots of her sullen and uncharacteristically bare face as she ventured out of hiding for frozen yogurt — revealed an unintentional gravitas. The event and its aftermath recontextualized Kardashian’s fame — perhaps fame itself for the modern era — exposing its real danger; it was reported that her assailants were able to track her whereabouts and appraise her possessions through her own social media postings.

Of course, regarding the mechanics of publicity in light of such a story seems besides the point. But the point itself is that fame touches real people, distorts their relationships, sells them out, even brings them to the brink of death. When Mina, ahead of the last set of performances of her career at the Bussoladomani club in Tuscany, was asked why she would abandon performing, she said “I’m afraid of the audience.” By finally creating such pronounced distance between the person and the celebrity, she loosened the constricting grip of fame upon her artistry, and reasserted her boundaries between person and persona.

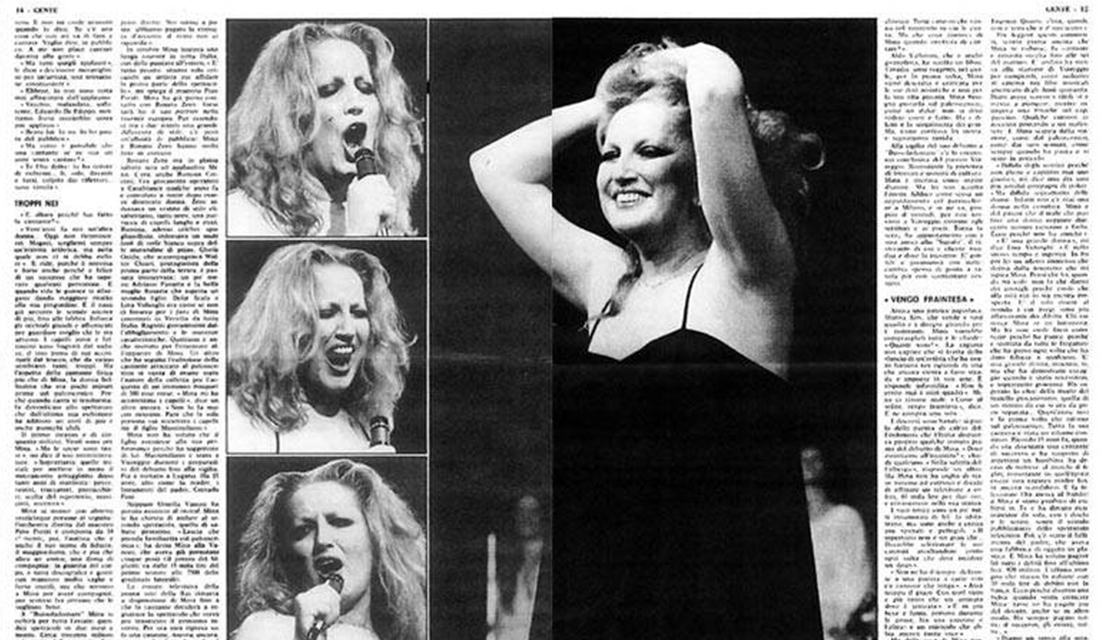

Coverage on the Italian magazine Gente of Mina’s last performance in 1978 | Source: © Mina Mazzini

We could use a little more of that now. We don’t want to see our icons disappear, but we do want them to remain iconic. Fame was once mediated by the press, but is now more democratically governed through social channels. The problem is that social media is performative but pretends to be real life. And this has made the celebrities — even the great artists among them — smaller.

When all culture is “content,” I think we should really be concerning ourselves with the level of intrigue that would-be celebrities are bringing to their fame.

Being withholding with fame — once you have it, of course — is a shock to the system. It’s a rejection of contemporary values: those which esteem visibility and the publicizing of private life. It’s a paradox which generates intrigue in absence and exposure in obscurity. It’s giving oneself fully and grabbing it back without warning, scattering images into iconography. It’s an avant-garde gesture that finesses fame and, in doing so, restores it to the domain of the artist and shields it from the corrosive effects of the limelight. Mina did not abandon public life as a stunt, a ‘social-media silence,’ a performative false-farewell. Indeed, she has never returned. But if more artists were to follow her example in at least concealing themselves, in “letting the work speak for itself,” it might make the world a little more interesting.

5 comments

That’s an interesting way of explaining thè IMPARAGONABILE Mina!

Amazing article! I’m Italian and I could tell you about a million things about Mina. Even the fact that she happened to distractedly throw away a card that Paul McCartney sent her in order to compliment her on the amazing version of the song “Michele” which she inserted in the album “MINA CANTA I BEATLES”.

A day or two after Paul McCartney sent the card, Mina’s son asked her if she knew where she had put it because he wanted to see it. But Mina replied (while cooking fish in the kitchen) that she thought she might have thrown it into the garbage can. Hahaha! Hysterical!!

I am an American Mina fan,I love her. I discovered who she was about ten years ago on youtube with a recommendation to watch Mina’s version of Barbra Streisand’s Minute Waltz,Questo Sette Cento,but it was Se Telefonando that made me a fan,now ten years and 50 Mina albums and hundreds of Mina songs later I like her more than ever. and with her new cd coming in November,color me excited.

I stumbled into this great article by checking what might Lennon would have thought about Mina.

As a little child (8), I was so into The Beatles, specially Lennon, so I had no time for Italian music (though my mom and her brother drove me mad making me listening to Mina and Di Capri all the time).

The years went by and don’t ask me how, sth triggered in my mind and out of the blue, I memorized all her lyrics (up to her 1978’s curtain down). And bit by bit one thing led me to another till I learnt almost all the Italian scene -and songs- from the 40’s to nowadays.

All I can say is that she is amazing, as I have always felt, the best female voice ever.

And Mina proves she’s still viable at 80,sge just has another hit song and a hit album with Mina /Fossati. and her two new redos are hits.