CHRISTA PLUFF

Pandas.

Note to the editors: We could just link to the National Zoo panda cam and call it a day.

Note to the readers: If you want to embody rather than read the next 2,000 words, just stop here, commence with the warm fuzzies, and think about how much you’re empathizing with these ridiculous creatures.

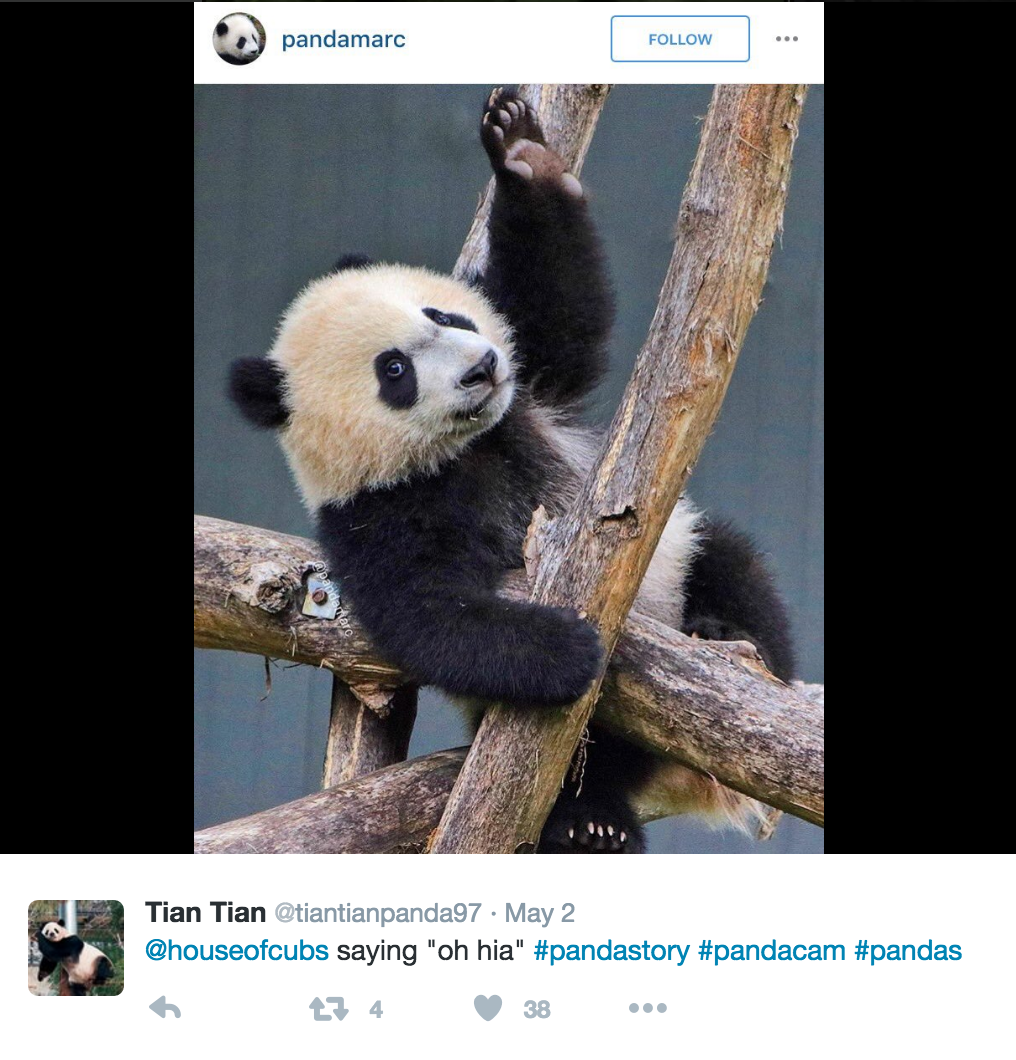

Bei Bei | Source: Tian Tian/Twitter

I’ve lived in Washington, D.C. for seven years and have been to the National Zoo perhaps four times, but couldn’t begin to count the number of instances I’ve come across a panda — not in person (in panda?), mind you, but encountered nonetheless. Take “PandaMania,” a 2004 public art exhibition that scattered more than 150 panda statues throughout the city. Or the ‘panda-outs’ regional media experienced in 2013 and 2016 when Bao Bao and Bei Bei, respectively, were born unto this earth and forever cemented in our collective consciousness. Or, most importantly, the aforementioned panda cam, which brings Tian Tian, Mei Xiang, and the whole panda clan right to your fingertips. Perhaps you yourself haven’t experienced the glorious panda cam, but I once had a coworker who tempered the absurdity of our office by keeping the live-stream up on her phone throughout the workday — a sort of “panda shui,” if you will, and a service which, I should mention, could be yours for $1.99 from your friendly local app store.

Maybe pandas aren’t so much a thing outside of D.C., but animal videos in general most certainly are. You’d be hard-pressed to visit any social media site without stumbling across at least one instance of an animal sneaking food, or tumbling through the snow, or crying in joy as it reunites with a long-absent owner, and why not? Who couldn’t use an injection of uncomplicated cuteness into their day?

The answer is none of us.

Research has found that humans are instinctively attracted to anything vaguely resembling a baby: big eyes, big cheeks, and big heads, with bonus points for a disproportionately tiny body. Prince George, Lil BUB, Volkswagen Beetles — doesn’t matter. We’ll eat it up. Since the 1940s, several researchers have sought to prove that this is a hardwired survival mechanism kicking in, telling us to save the human species by protecting our young, and it’s even accompanied by a dopamine rush — our brain’s way of apologizing for that time we teared up over a lamp in an IKEA commercial, but also for ensuring that we continue to love our children even at their brattiest.

Lil BUB | Source: Lil BUB/Twitter

In addition to the anthropomorphizing we instinctively do by exaggerating human-like physical qualities in animals, we also have a tendency to “egomorphize” — that is, to believe that animals inherently share self-like qualities, such as cognition and emotion as we understand them. The authors of a 2013 study detailing egomorphization and its role in conservation have their own example to illustrate this, but I prefer to use the time a baby squirrel bit me on the foot because I thought he was interested in socializing, not simply on the lookout for its next meal and bewildered by the monstrous, hairless animal that had just blocked his path.

Who couldn’t use an injection of uncomplicated cuteness into their day?

Tiny Hamster Eating Tiny Burritos (Ep. 1) | Source: HelloDenizen/YouTube

In other words, it almost doesn’t matter what an animal’s doing — as long as it’s looking at us with those big, round eyes, all we hear is, “Help me!” We are hardwired to believe that nature, just going about its usual routine, is performing a need for nurture. Give us an adorable animal and our brains automatically dress it up in needy baby makeup and costuming as our innate suspension of disbelief fires up, ready to save the day.

Biology, take the wheel: we want to save the cute thing.

This is great news for conservation groups who aim not only to educate the public, but also to drive action. In addition to tapping into the empathy that comes from putting animals right in front of viewers, videos can increase email open rates by up to 13%, make it 53 times more likely that a site appears as a page-one Google search result, and boost actions like signing petitions or making donations by 46%. In citing these stats, Conservation Media Group also points to a report done by Millward Brown Digital and Google noting that 75% of donors use video to understand the impact of a nonprofit organization before giving. That’s all we need to know, right?

Not so fast.

Araiguma Rasukaru | Source: Wikimedia Commons

In the 1970s, hundreds of raccoons were imported as pets each year in Japan after the success of the anime series Araiguma Rasukaru (Rascal the Raccoon), based on an autobiographical novel in which author Sterling North details the year he spent raising a baby raccoon. It should be noted that North grew up in rural Wisconsin during World War I, a setting in which, perhaps, a young boy adopting a raccoon might be expected, if not cause for celebration. It should also be noted that part of the moral of the book was that, just maybe, wild raccoons don’t make great house pets: in the end, North recognizes that Rascal can never be the human companion (or, at the very least, the domesticated pet) he’d like, so he releases him back into the wild. Rasukaru, however, is cute, clean, and caring, and raccoon fever spread. Fast forward to Japanese households pulling a North when their newfound raccoon friends were more Rascal than Rasukaru, and the resulting nationwide raccoon eradication program.

Slow loris loves getting tickled | Source: hamlollo/YouTube

Unfortunately, sometimes it doesn’t even take animation to turn an animal into the latest pet craze — often the death knell for its kind. Slow lorises, a group of several species of nocturnal Southeast Asian primates, attracted a huge YouTube following in 2009 when a video of a loris being tickled went viral. This particular video now has more than six million views, and why not? Those round, peaceful eyes. That slow, wistful arm drop just screaming, “Please keep tickling me!”

The problem is that “peaceful” and “wistful” are my own read of the situation, not an inherent truth — and this is dangerous territory in an age when video can be uploaded and shared at the tap of a screen. In a TEDxNashville talk, Dr. Anna Nekaris, a professor in primate conservation and anthropology at Oxford Brookes University, suggested that the loris we see being tickled by its owner is not enjoying itself — instead, it’s passively submitting as a defense mechanism. In another popular video where a loris is seemingly enamored with its new toy, a cocktail umbrella, the more likely explanation is that the animal, possibly dealing with a head wound, is desperately grasping for what it hopes is bamboo as it’s effectively blinded by daylight. That these videos exist at all is somewhat surprising, as the journey to get to their new domestic dwellings subjects lorises to a high chance of death in transit. This mortality rate is often the result of having their teeth pulled or cut — their bite is toxic, after all — resulting in severe bleeding, dental infection, and malnourishment. Despite this, the export market is booming, with lorises selling for thousands of dollars in the U.S., across Europe, and — like the raccoon — in Japan.

The problem is that “peaceful” and “wistful” are my own read of the situation, not an inherent truth — and this is dangerous territory in an age when video can be uploaded and shared at the tap of a screen.

Cute animal videos encourage us to open our hearts, our minds, and even our wallets, but sometimes it’s to buy an animal, not to make a donation. In considering how we got to this place of tension between helping and having nature, it’s easy to point to industrialization and call it a day, but what’s a piece rooted in performance without a little criticism of white, male-centric Christian European world views? For kicks, let’s look to Carolyn Merchant, an eco-feminist philosopher at UC Berkeley famous for her theory on “The Death of Nature.”

Perhaps the most famous of Merchant’s example of a 17th-century French ‘mechanist’ (philosophers who explain nature purely based on mechanics), René Descartes | Source: Wikimedia Commons

In her book of the same title, Merchant tells us that we have 17th-century French ‘mechanists’ to blame for our current sense of removal from the natural world. Prior to the Enlightenment, nature was both respected and feared as the unknowable mother of all things. Then came the Scientific Revolution and a parade of scientists set on eschewing the role of religion in the natural world, but also applying a Christian fundamentalist view toward its control — in other words, the simultaneous “despiritualization” and “Biblicization” of nature. At the center of this is Francis Bacon, who advocated that the dominion over nature granted to Man by God at Creation, then subsequently lost in the Fall (thanks, Eve), could be reclaimed through empirical science, putting humanity back on track toward the Second Coming of Christ. Occurring in tandem with the rise of capitalism and industrialization, this view that nature could be entirely known and controlled by humans decimated our relationship with the environment.

Note to the readers: Merchant takes care to point out Bacon’s use of female metaphors in describing the exploitation of nature; just as a little reminder that even the birth of modern science was complicit in supporting ye olde rape culture.

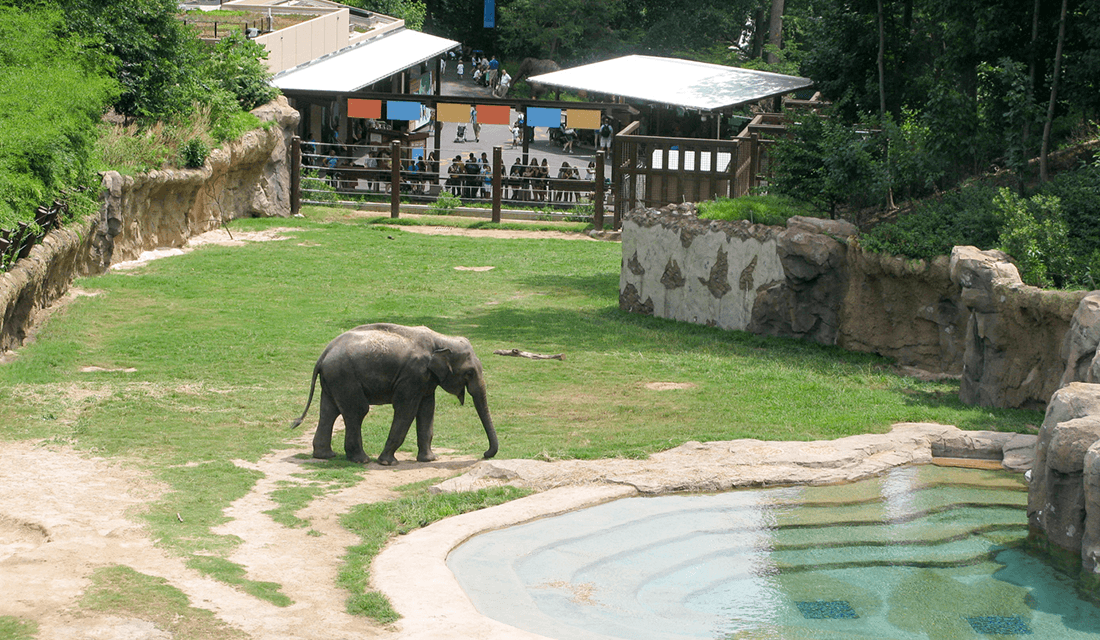

So here we are, four centuries and one ongoing mass extinction later. The question now is how we can best navigate this tension between having and helping nature— tilting the scales in favor of the latter — and we might look to research on zoos for guidance. PJA Architects, a Seattle-based firm specializing in zoo design, puts it best: “A funny thing happens when you put animals in a natural environment, they act natural.”

As part of a series on how zoos and aquariums can foster cultures of care and conservation, social psychologist Susan Clayton speaks to the importance of enclosure design in determining visitor attitude toward displayed animals. Concrete, barred enclosures in which visitors look down at the animal — or traveling circus wagons like those still used as the box design for Barnum’s Animals Crackers — set the stage for immediate objectification; after all, if an animal’s keepers deem it appropriate to trade natural habitat for barren digs designed for easy viewing, who are we to say otherwise? Alternatively, a spacious, natural-looking enclosure does four things: provides better conditions for the resident animal to act as it would in the wild, serves as a constant reminder that the animal comes from somewhere else, posits that this “somewhere” — let’s call it a ‘home’ — is important to the survival of the animal, and subsequently makes the case that the preservation of said home is as worthwhile a cause as that of the animal. In short, our “managed” encounters with nature work best when we situate wild animals in — you guessed it — the wild.

The PJA Architects-designed Asia Trail II in the National Zoo at Washington, D.C. | Source: © PJA Architects

Clayton also speaks to the role of exhibit signage in calling attention to connections between visitors and animals — that “animals play, sleep, and have families;” that “gorillas have fingerprints, too” — an action that builds empathy through shared experience, playing up our tendency toward anthropomorphization and egomorphization. They also, of course, aim to build empathy through purely factual education, something for which loris expert Nekaris hopes community-governed media-sharing sites such as YouTube will assume more responsibility. In coding the comments left on loris YouTube videos, Nekaris and her team noticed that conservation sentiment grew exponentially when information about illegal trade made it on to the slow loris Wikipedia page — an entry that was written in response to the first video, and quickly became the most viewed animal page after the video went viral. The hope is that such context — such ‘dramaturgy,’ if you will — will give viewers the information they need to best police content, removing dangerous videos and leaving more space for conservation-minded media to flourish.

Concrete, barred enclosures in which visitors look down at the animal set the stage for immediate objectification; after all, if an animal’s keepers deem it appropriate to trade natural habitat for barren digs designed for easy viewing, who are we to say otherwise?

So now we come back to pandas.

These big, lovable bears are a multimillion dollar venture for China, which leases them to international zoos for big bucks — the National Zoo in D.C. forks over $500,000 annually for the panda squad gracing Adams Morgan. While much of this money goes to maintaining zoo-specific exhibits and programming, a significant amount also supports continued wild panda conservation efforts, and U.S. federal policy requires participating zoos to go further by actively participating in research to advance captive breeding, habitat preservation, and reintroduction. The craziest thing, however, is that there are people out there who elect to fund all of this on their own. In 2011, D.C.-based philanthropist David Rubenstein gave $4.5 million to the panda program at the National Zoo, a gift he renewed in 2015 to not only support research and conservation efforts, but also upgrade the habitat — which carries his name — that houses Tian Tian, Mei Xiang, Bao Bao, and Bei Bei.

Pandacam shot of Mei Xiang and Bei Bei | Source: BaR21RmZ/Twitter

Bei Bei, again | Source: Tian Tian/Twitter

Why? Because they’re so cute — that pandas “bring joy to millions” was cited by Rubenstein himself in discussing the factors behind his philanthropy — but also because the panda program is comprised of several strong components working together to support conservation efforts. Behavioral research, ecological studies, a strong #pandastory following on Twitter, a family-newsletter-style giant panda bulletin, and even an adopt-a-species program to sate our Baconian ‘have’ tendencies provide all the pieces we need to understand not only the pandas, but the role we can play in saving them. And, of course, we have the panda cam, allowing us to ‘o-o-h’ and ‘a-h-h’ at their sweet baby faces tumbling about their lustrous wild-like habitat as we click through all of this, learning and anthropomorphizing and egomorphizing along the way. All of this combined is the reason Motherboard recently argued that we can’t save anything if we can’t save pandas, a seemingly sound point. If we can’t leverage all of this — most of all the cuteness — what are we doing wrong?

Long live the panda cam.