ZÖE GIELOW

A year ago, an unremarkable American dentist from Bloomington, Minnesota travelled over sixteen hours to the grasslands around the Hwange National Park of Zimbabwe. He had all of his papers in order — a hunting permit from CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), a registered guide licensed by the Zimbabwe Ministry of Environment and Tourism who was knowledgeable with the area’s boundaries and laws, a confirmation that no permit was needed from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for his plans, a permit for bow hunting, and a temporary export license for his weapons and ammunition, cleared through customs. Under cover of night, the man legally and lawfully shot and wounded a large male lion, continued tracking him for over 40 hours, and successfully killed, skinned and decapitated the animal.

Cecil the Lion | Source: Daughter #3/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Walter Palmer’s killing of Cecil, a well-known and beloved lion in the Hwange National Park, sparked international outrage that lasted for months. Activists called for his immediate extradition, some demanded him to be brought to justice for the murder, and a few published his private address and information, and even delivered death threats. Celebrities, government officials, and politicians condemned his actions, and mourned the loss of Cecil. The lion was a large draw to tourists in the park, and was additionally part of a years-long study by the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit at Oxford University. The outpouring of outrage and grief led to an international debate on the mission, benefits, and laws surrounding trophy hunting.

Source: UA Archives/Flickr

Trophy hunting refers to the permitted hunting of large wild game for recreational purposes. Although it is extremely popular in Africa, particularly regarding big cats and elephants, the practice is in full force all over the world. The politics of the practice are both nuanced and charged, with those in support and those in opposition vehemently denying the points of the other side.

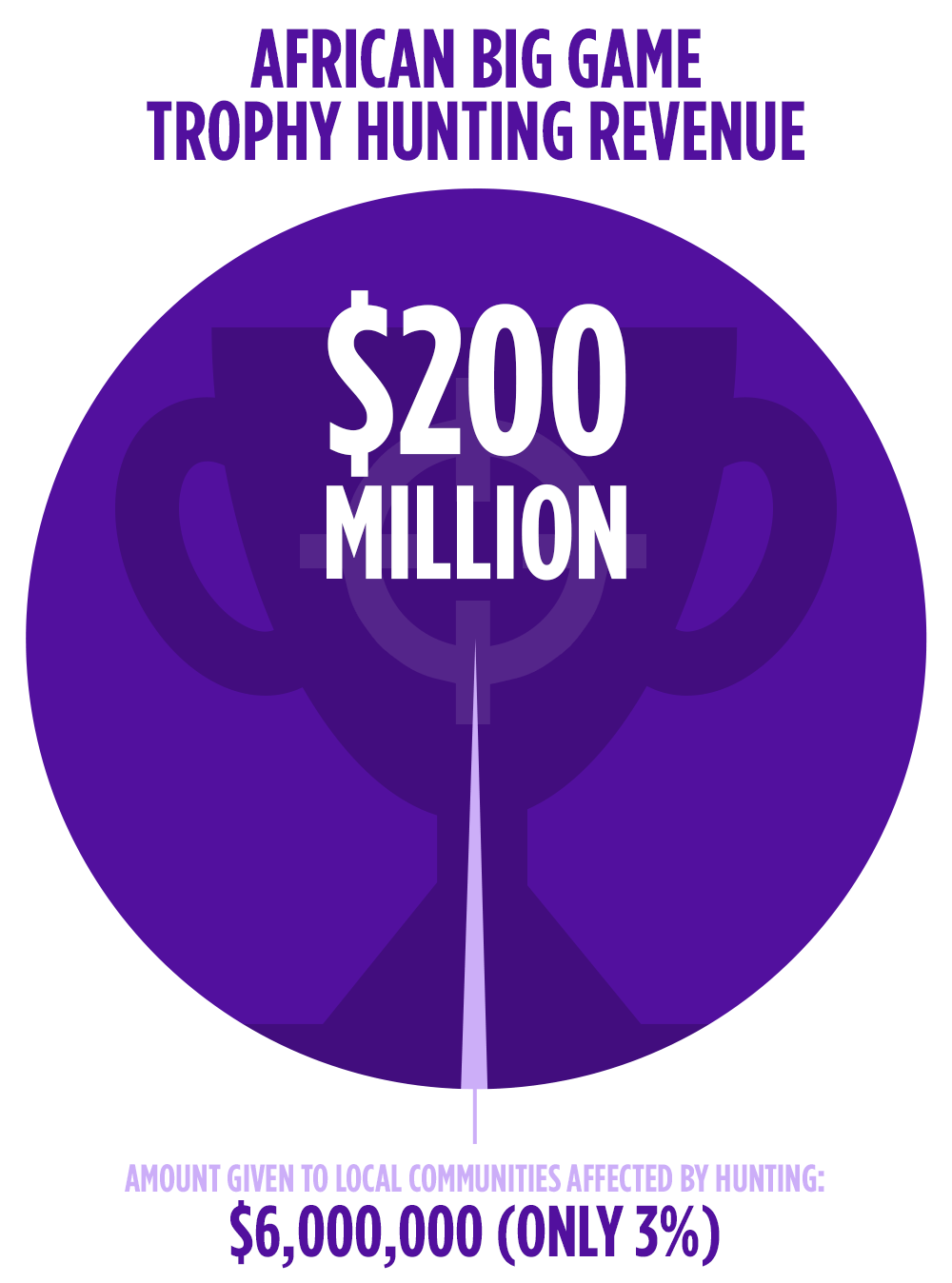

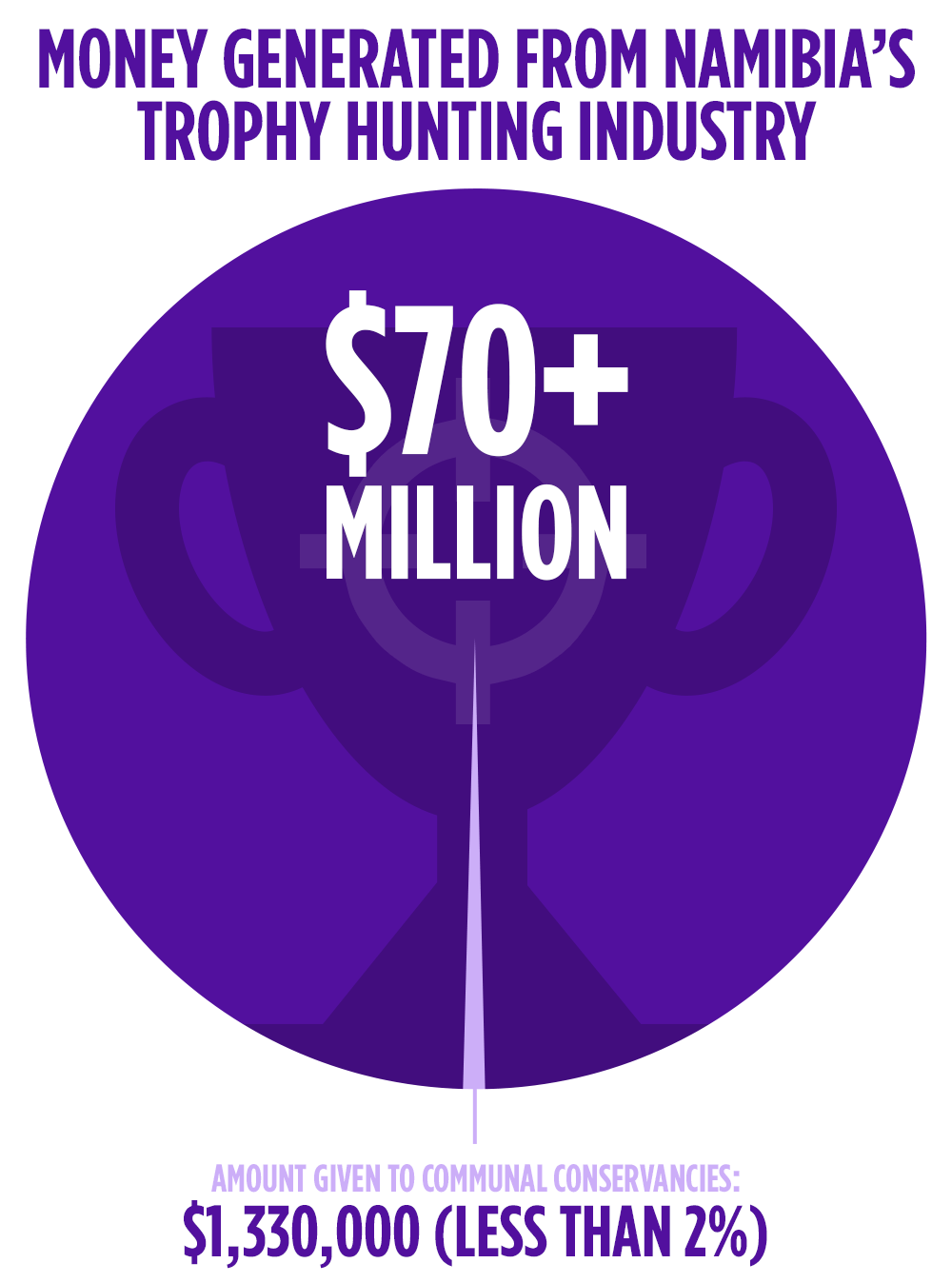

Those in support of trophy hunting often make strange bedfellows — from the Safari Club International to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, from the National Rifle Association to the World Wildlife Fund. These supports say that the permits bought by trophy hunters can cost up to $100,000 each, and a portion of those proceeds is donated to conservation efforts. Each permit is auctioned off to the highest bidder, and the rarer an animal is, the higher the price will be. The influx of money also gives the local economy a boost, and can create jobs in poverty-stricken areas. Safari Club International, the organization that licensed (and later suspended) Walter Palmer to hunt in Zimbabwe, stated that the practice of trophy hunting employs over 53,000 people and contributes $426 million to various Sub-Saharan African countries. The hunters coming into Africa can spend up to $30,000 per trip, often in rural and poverty-stricken areas. Those in favor also say that these big-game hunters are an important part of keeping these animal populations healthy. Officials and guides usually help hunters target animals that are either past reproductive age or actively disrupting the reproductive and social interactions of the species. The president of the Dallas Safari Club, Ben Carter, commented that “by removing counterproductive individuals from a herd, [populations] can actually grow.” Overall, the practice of regulated trophy hunting, when executed perfectly, could provide huge benefits to the species, the ecosystem and the local community and government.

However, it is rarely practiced perfectly. Even without including the drawbacks of a perfect system, trophy hunting is too easily corrupted, either regarding the amount of licenses issued, the veracity of the permits themselves, the targets of the hunters, and the distribution of the money.

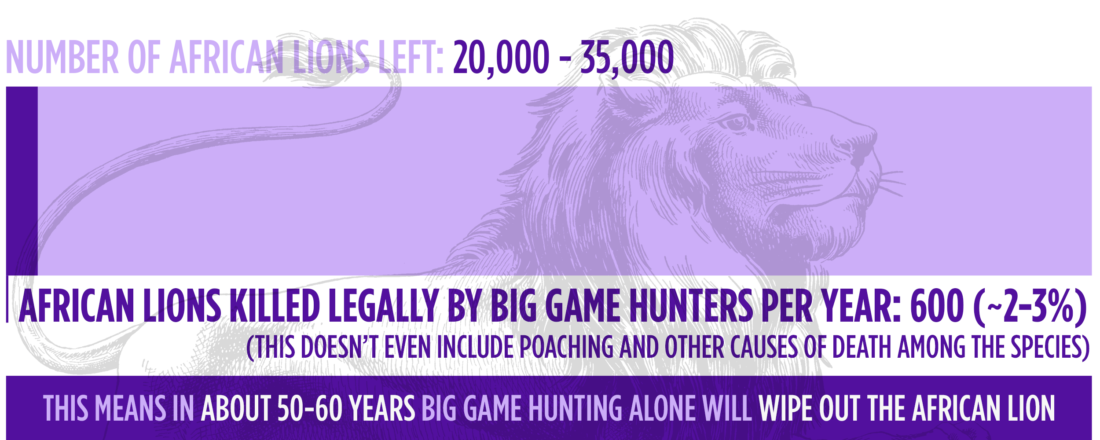

Source: The Dodo

Those who oppose trophy hunting do so for many different reasons. Some believe that hunting for sport alone is inherently immoral, and should not be tolerated. Even in ranch hunting, where animals are specifically bred and raised for hunting purposes, those who oppose state that the animals are still endangered, regardless of how they were raised, and any killing is detrimental to their endangered status. Additionally, continuing to add trophies such as heads, antlers, skins or skeletons of these animals to the hunting population can only lead to a higher demand of said trophies. Even those who agree with the theory of trophy hunting can disagree with the actual practice. In Cecil’s case, the lion was never supposed to be targeted, as he was not only living on a protected reserve, but additionally was the head of a large pride. The killing of the dominant male of a large pride can be catastrophic for the species, as outsider males will not only kill each other while vying for the right to lead the pride, but they will also kill the cubs of the pride to make way for their own.

Source: National Geographic

Trophy hunting negatively impacts the evolutionary processes of the species as well. Although permits are usually issued for older individuals past reproductive age, who do not contribute to the social interactions of the group, in practice, this does not hold up. Trophy hunters often target the largest, most dominant males of any animals, killing them before they have had the ability to pass on their genes to the next generation. This artificially limits the gene pool, weakening the overall genetic robustness of the species. Hunting these individuals can also affect the tourism and economy of the area. Well-known, large animals, such as Cecil, can be a very effective draw for tourism. It was estimated that the money in five days raised from tourists going on a photographic mission to see Cecil would have been greater than the money paid by for the hunting permit, and would have been able to continue to generate future revenue. Even the specific money earmarked from the permit for conservation can often amount to less than 10% of the overall cost, negating the benefits. Cecil the lion was a single case in the ongoing practice of trophy hunting around the world. Although regulated trophy hunting is, in theory, a well-rounded system with many benefits, in practice, these benefits are too often corrupted, and do not outweigh the drawbacks.

Source: State Archives of North Carolina Raleigh, NC/Flickr

In this day of divisive politics, any hot-button political issue always involves posturing on both sides. Along with those who passionately and genuinely care about the issue, there are those who join one side due to any number of reasons — political constituents, pressure from donors, hometown loyalty, white savior attitudes, or even the simple fun of Internet outrage, a trend that has grown more common with the rapid response abilities of the online collective (#hasjustinelandedyet being a good example of the last two combined). On the other side, the entire model of trophy hunting can be considered posturing in itself — having a room of hunting trophies is tangible proof of a wealthy, strong, often hyper-masculine lifestyle. Both sides of these types of arguments are filling roles and one-upping themselves and the opposing side, one with the cyclical comments and actions of environmental activists (“Trophy hunting is less important than endangered species conservation is less important than global climate change is less important than…”), and the other with the cyclical manner of hunting trophies and the alleged benefits along with it (“A six-point rack is less impressive than a rhino’s horn is less impressive than a lion’s head is less impressive than…”). This kind of disingenuous rallying on both sides can be found in all environmental issues today that lack a bipartisan solution, from endangered species conservation to the bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef to the overarching question of global climate change. Although many of these problems have a scientific consensus on the way forward, too often they turn into controversies to be used by politicians, activists, and governments at will.